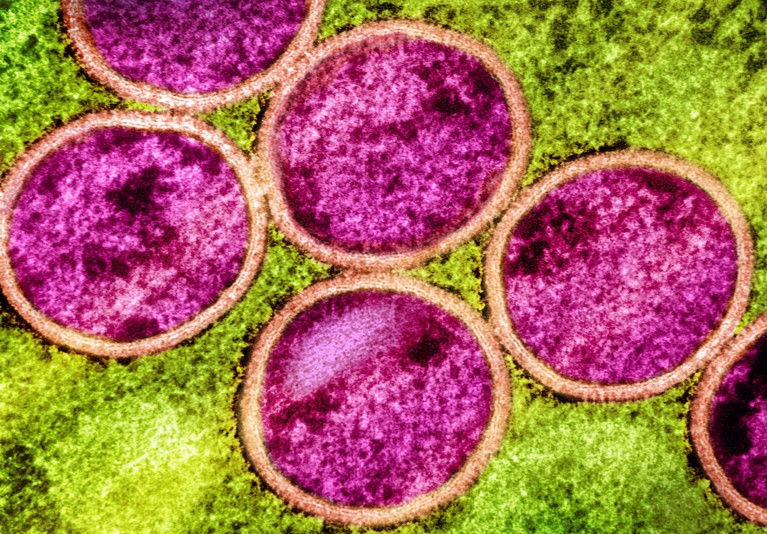

Mpox virus particles (purple) seem to be spreading more easily between people.Credit: NIAID/SPL

As mpox continues to spark localized outbreaks in Africa and, on occasion, in other parts of the world, researchers are racing to understand how the virus managed to spread globally in 2022 — and how it might do so again.

A study published in December found that the strain that caused the 2022 outbreak persisted in the testes of mice for weeks after infection and caused tissue damage1, highlighting the possibility that the virus could impact male fertility. This has not yet been studied in people.

The study was posted on the preprint server bioRxiv and has not yet been peer reviewed. Meanwhile, the virus continues to evolve. In December, health officials reported a strain of the mpox virus that combines genetic elements of two existing types, or clades, for the first time. Although it is normal for viruses such as mpox to evolve, the more opportunities they are given to spread, the more likely they are to eventually evade protection from vaccines and treatments.

Taken together, these data show that scientists “still have a lot to learn” about existing strains, let alone new strains, says Boghuma Titanji, an infectious-disease physician at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. Mpox belongs to the poxvirus family, which also includes smallpox, “so we should not underestimate what it can do if it’s allowed to become firmly entrenched in human populations and continue to adapt”, she adds.

Mpox is evolving

Mpox infections can cause painful, fluid-filled lesions on the skin, fever and, in severe cases, death. There are four known clades of the mpox virus: clades Ia, Ib, IIa and IIb (see ‘Quick guide to the clades of mpox virus’).

The virus has been infecting humans since the 1970s. Historically, it rarely spread widely, but this all changed in the late-2010s, when a clade II strain caused a large outbreak in Nigeria. A similar clade IIb strain sparked the 2022 global outbreak, in which more than 100,000 people were infected. It is still ongoing.

In 2025, there was a large increase in infections with clade I mpox, which historically caused sporadic but deadly outbreaks in rural parts of Central Africa. A new subtype of clade I, called Ib, began spreading between people in dense urban areas in late 2023, possibly through sexual contact. This spread has worried scientists because the sudden emergence of clade Ib mpox mirrors the trajectory of clade II before it went global, Titanji says.

Mpox is spreading rapidly. Here are the questions researchers are racing to answer

Over the past couple of years, researchers have been racing to understand how the new mpox clades, Ib and IIb, differ from their predecessors. Data from rodents infected with mpox offer evidence to support a theory that these clades are less lethal but more adept at spreading from one person to another because they cause milder illness2.

Rats infected with clade Ib mpox had higher survival rates than those infected with clade Ia, yet they transmitted just as much infectious virus. And the onset of visible skin lesions was significantly delayed in clade Ib infections, the researchers found.

These findings help to explain why the virus “might be quite efficient in spreading through sex”, as people could be unknowingly transmitting the virus before they are symptomatic, Titanji says.

Fertility issues?

Another group of scientists studied how clade IIb mpox infects mice1. They found high levels of infectious virus in the rodents’ testes for at least three weeks after infection, suggesting that the male reproductive tract might act as a reservoir for the virus, and helping to explain why the virus is so efficiently transmitted through sexual contact.

The infection caused tissue damage that led to the loss of sperm production, the researchers found.

“We were expecting to see some inflammation or disorganization, but to see that potentially this infection was affecting male fertility was shocking,” says study co-author Alyson Kelvin, an emerging-virus specialist at the University of Calgary in Canada.