Posted on: August 12, 2024, 05:32h.

Last updated on: August 12, 2024, 08:55h.

On April 30, 1968, Howard Hughes purchased the Silver Slipper for $5.4 million from an investment group led by Maurice Friedman, T.W. Richardson, and Shelby Williams. (Yes, all had ties to organized crime.)

The sale did not include Hughes’ favorite thing in the building, however.

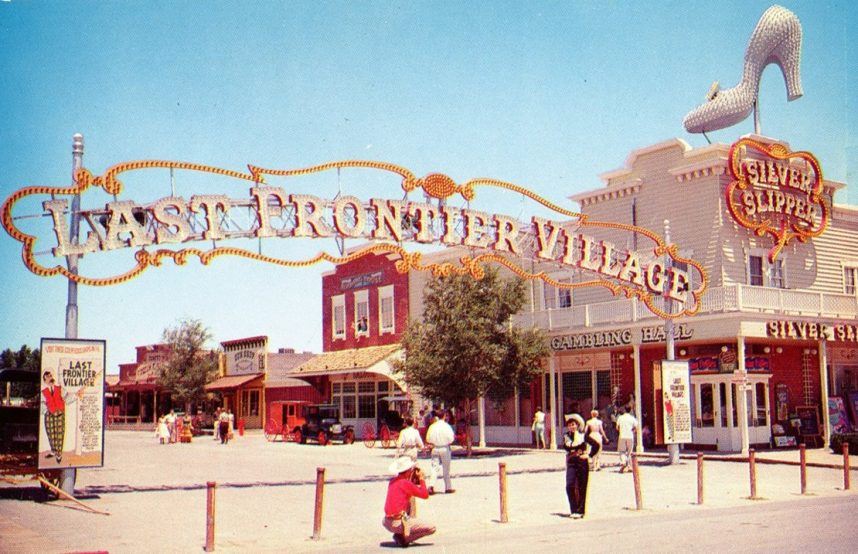

That’s not a reference to the famous high-heeled slipper sign spinning around on top of it. Hughes didn’t love that, but he didn’t hate it either. (Specifically, Hughes did not purchase the Silver Slipper just to dim the sign, despite a persistent myth we busted to the contrary.)

What Hughes loved was the artwork — 33 oil paintings hanging throughout the property created by Julian Ritter.

Lost Art

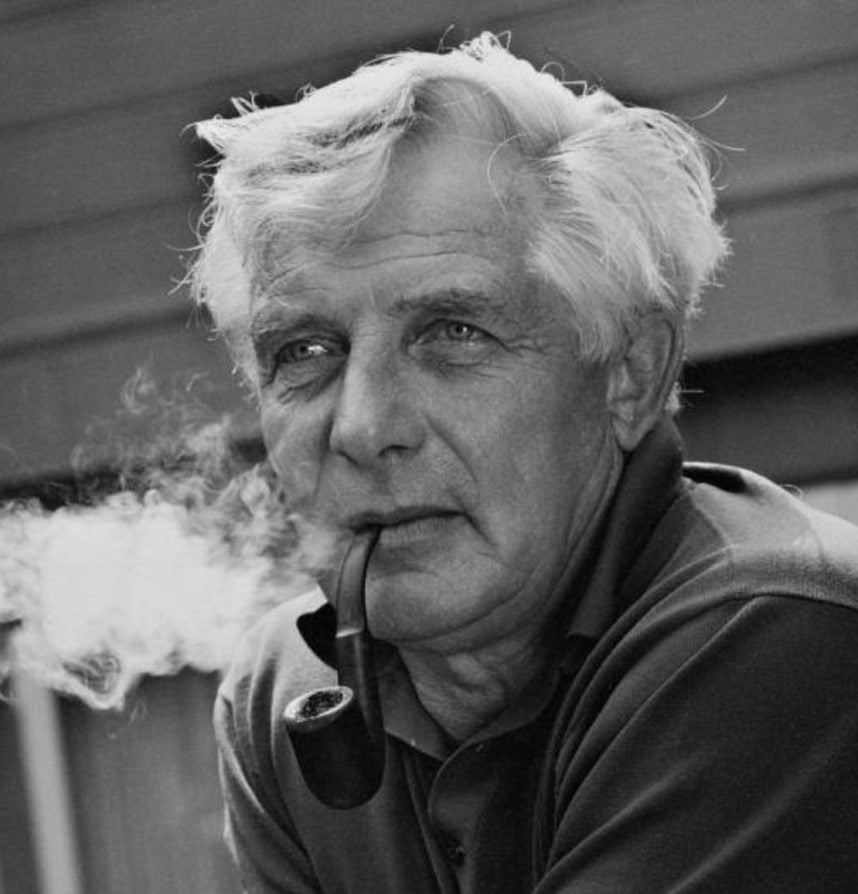

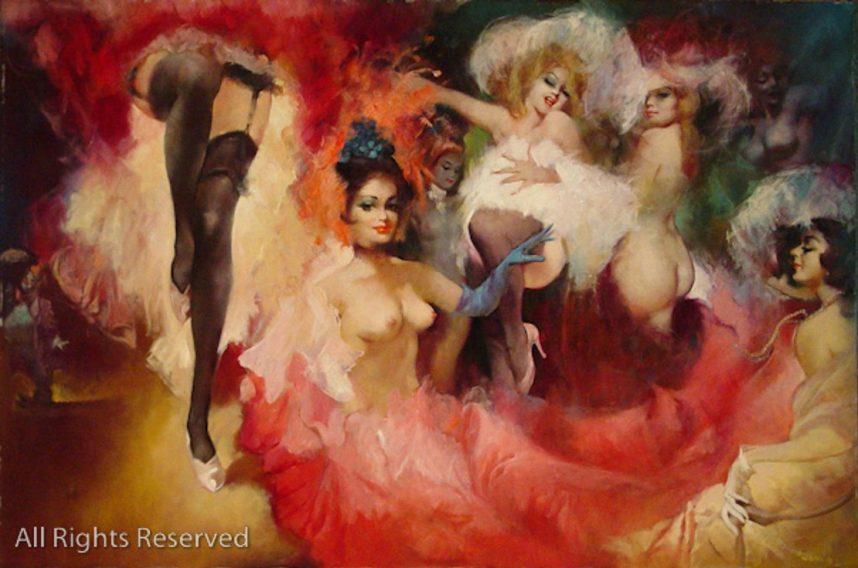

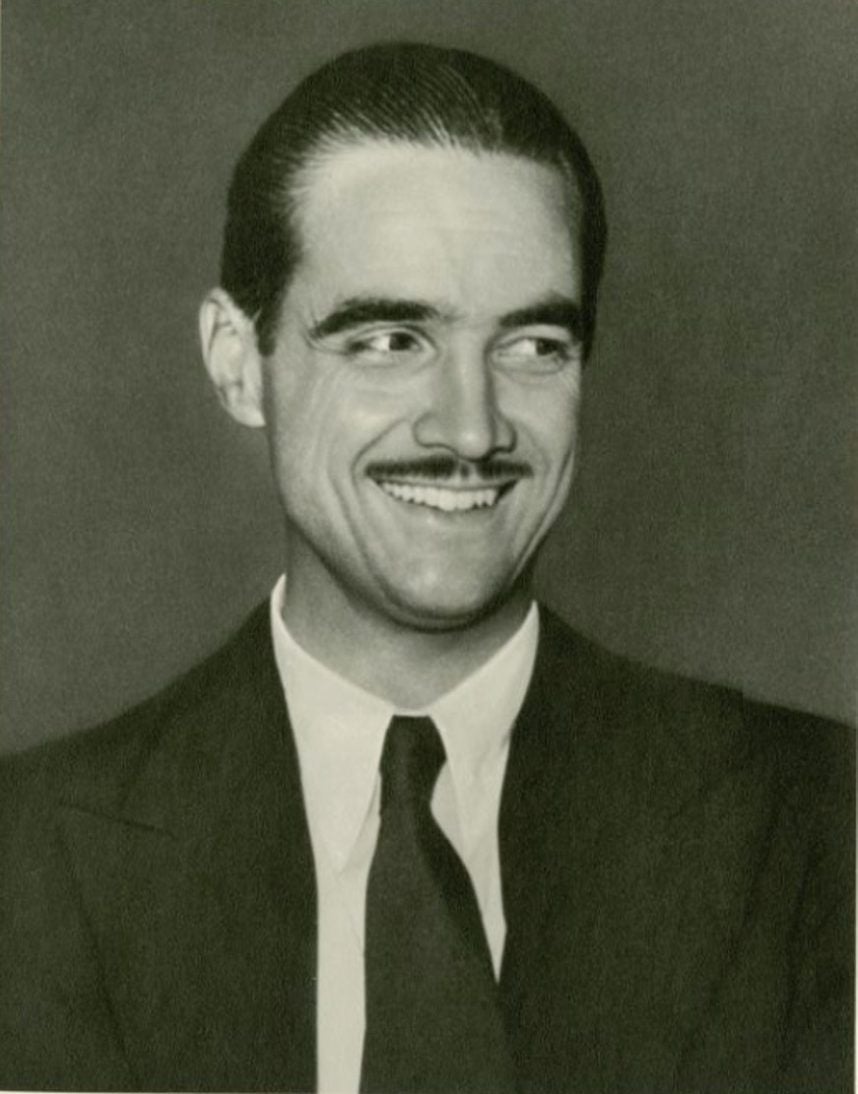

Julian Ritter was a 20th-century painter known for his vibrant and often provocative female nudes, showgirls, and clowns.

“Julian painted using glazes on his skin tones that brought out luminosity in the flesh reminiscent of the great masters of the Renaissance,” Greg Autry, the world’s foremost collector of Ritter’s work, told Casino.org. “His paintings had a vibrancy. People would line up at the Silver Slipper just to look at them.”

Most of the paintings displayed by the Silver Slipper were purchased by Autry and have sat in storage since he got divorced in the ’90s — well, minus the five that were “taken as mementos” by Hughes-employed casino managers before his purchase, Autry alleges, and the six his ex-wife took as mementos of their divorce settlement.

That leaves Autry with 22.

Ritter began his career painting sets for the Warner Bros., MGM, Paramount, and Universal movie studios in the mid-1930s. On the side, he accepted commissions for the movie stars he met — including Jimmy Stewart, Olivia de Haviland, Claudette Colbert, and Veronica Lake — to paint portraits for their homes.

In 1941, two major New York exhibitions finally earned Ritter the notoriety with the general public that he craved. And in February 1950, at the urging of his brother-in-law, the artist took a road trip with him to Las Vegas to try and sell his work to casinos.

“He had a lot of success by then, but like any artist, he was always looking to sell more,” Autry said. “They were sitting in Julian’s backyard in Woodland Hills having drinks when his wife’s brother came up with the idea.

“There were a lot of hotels and casinos being built in Las Vegas and they needed all art.”

Ritter’s 1949 Dodge Wayfarer had no backseat, but they crammed its trunk with 13 of the best paintings Ritter had on hand at the time. The two went from casino to casino on the Strip without any success until they met Bill Moore.

The owner of the Last Frontier fell so hard for Ritter’s paintings, he bought all 13 for $1,000 ($12,500 today) and commissioned 10 more to hang in the new casino he planned for the Last Frontier Village, a mock-up Wild West town of old-timey shops and gunfight re-enactments that Moore opened on the grounds of the Last Frontier in 1950.

The Auction That Wasn’t

The Silver Slipper’s art collection has not been seen publicly since October 1988. That’s when, according to every article written about them since, Autry won them in a closed auction.

Except that this auction never took place. Instead, Autry, who earned a good living in Southern California’s booming 1980s commercial real estate market, drove to Hughes’ Summa Corporation office with a U-Haul and a cashier’s check.

He won’t say how much it was for, but it was enough to get the auction canceled.

“I laid the cashier’s check face up, facing the receptionist, on her desk,” Autry said. “She looked down at it and her jaw dropped. After she regained her composure, she picked up the check and excused herself as she took the check to the offices in back.”

She disappeared for 45 minutes.

“I’m sure they were checking to see if the check was real,” Autry said, “and when she came back, she said, ‘Thank you, Mr. Autry, you bought yourself some paintings, and you have to have them out of there in 72 hours,’ which is when the demolition was scheduled to begin.”

Margaret Elardi had purchased the Silver Slipper that August. She decided to knock it down so it could become a parking lot for the Frontier, which she also owned.

When Autry entered the doomed 38-year-old casino for the first time, he was greeted by two massive Ritters high in the entryway. One was of a reclining nude and the other of multiple topless showgirls. He said they created “the biggest state of awe in my life.”

Another emotion that struck him at the time was disgust.

“I couldn’t believe how neglected and uncared for this amazing art was,” he said. “The paintings, which smelled of tobacco, had all been screwed to the walls to prevent people from stealing them. Some had their frames nailed in with railroad spikes. And others were covered with acrylic because of the booze that flew during bar fights.

“I spent years having them cleaned and their frames restored.”

The Art of Friendship

Autry was a superfan of Ritter’s who made his first purchase of the artist’s work in 1983 at a prominent Laguna Beach, Calif. gallery, which had priced it at $13,000.

“I got the guy down to three-thousand and thought, ‘Man, I am really good,’” Autry said.

Through some pre-internet research, Autry discovered that Ritter was still alive and residing in Santa Barbara. He used his purchase to wangle himself an invitation for his wife and him to meet Ritter at his house.

When they unwrapped the painting, seeking Ritter’s reaction, it was not what they anticipated.

“You’re a dumb(expletive), aren’t you?’” the artist asked Autry.

The painting was a fake, but not the nearly 20-year friendship it instigated.

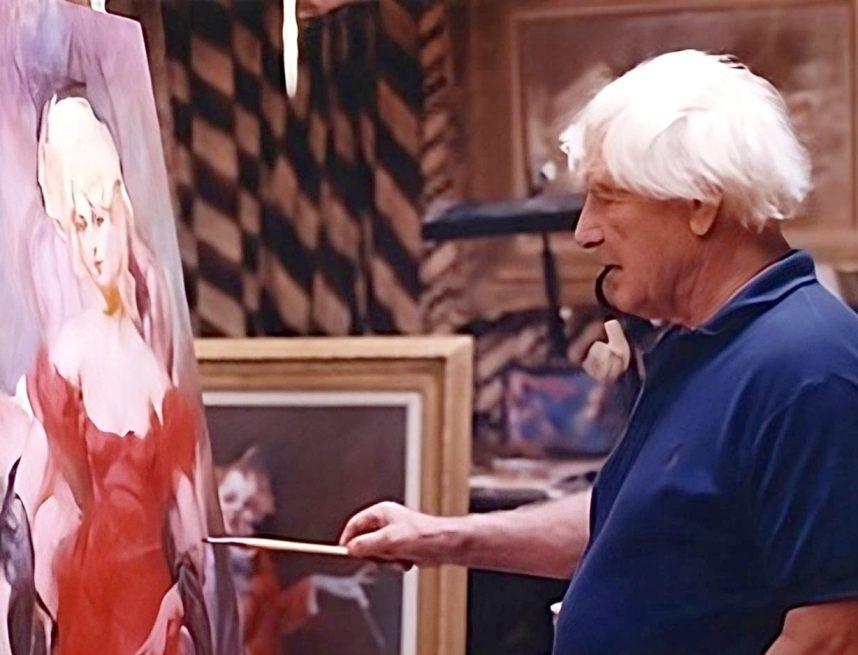

“We went up there almost every weekend,” Autry recalled. “I often took my kids and my wife, sometimes just myself. I’d sit in the studio and he’d paint and we talked and about painting, classical music, World War II, the Silver Slipper, showgirls.”

A few months after Autry purchased the paintings, Julian and his son, Michael, came to see them. At the time, they were displayed in the Culver City house Autry shared with his wife.

“I promised Julian that I would take care of them and treat them with the respect they deserved,” Autry said. “And I have honored my word.”

No Honor Among Thieves

When Bill Moore sold the Slipper to Friedman, Williams, and Richardson for $5 million in 1964, the sale included all of its 33 Ritters.

Hughes, however, had to pony up separately for those. Right after he bought the casino, its previous owners removed the paintings, claiming they were personal property and not part of the sale.

Hughes took them to court and won, according to Autry, but the judge stipulated that the owners had to be compensated for the paintings’ current value. (Ritter was among the people consulted by Hughes during the appraisal process.)

On Oct. 28, 1970, the billionaire negotiated the sale for $471,000 ($3.3 million in today’s dollars).

Hughes died in 1976 at age 70. Ritter died in 2000 at age 90. The Silver Slipper is now a vacant lot on the south side of Resorts World. And Autry, who at age 76 is focusing beyond his own remaining years, wants the long-gone casino’s former art collection to find a home where it can be enjoyed again.

“I’d like to sell the paintings, but I don’t want to sell them individually,” he said. “I want to sell them all to somebody who will appreciate them and let them be seen by the public in the right kind of environment again.”

Autry said that interested parties can find his contact information by clicking “connect” at www.julianritter.com.

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series spotlighting Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.