We like to think that we know what the Second World War was fought for: freedom, democracy and the defeat of Germany and the evils of fascism. Compared to subsequent conflicts, the aims of the war seem self-evident and straightforward. But back in 1939, none of this was clear.

Faced with a war he had desperately sought to avoid, no one was more tight-lipped about war aims than the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain. Concerned about alienating potential allies – how, for example, would a battle for ‘Christian civilisation’ sound to the atheistic Soviet Union – and fearful that bellicose demands might prevent a German domestic revolt against Hitler, Chamberlain chose a combination of silence and platitudes as his communication strategy.

Politics, like nature, however, abhors a vacuum. Between the declaration of war in September 1939 and the German invasion of France and the Low Countries in May 1940 – the so-called ‘bore war’ – plans for the postwar world dominated the political conversation. These included everything from ideas about new systems of international law, advocated by the newspaper editor Walter Layton, to the Labour intellectual G.D.H. Cole’s plan to abolish international capitalism, via the dreams of the radical lawyer Richard Acland to reorganise political life along Christian principles.

Given the Conservatives’ support for national sovereignty and distaste for political utopias, we might imagine that they would be exclusively hostile to these kinds of radical ideas. That was not the case. While there were those who bemoaned these ‘brave new worlders’, others were more sympathetic and put forward bold ideas of the future. Alongside support for European political integration and a revived League of Nations, some even supported the most utopian idea of the era: world government.

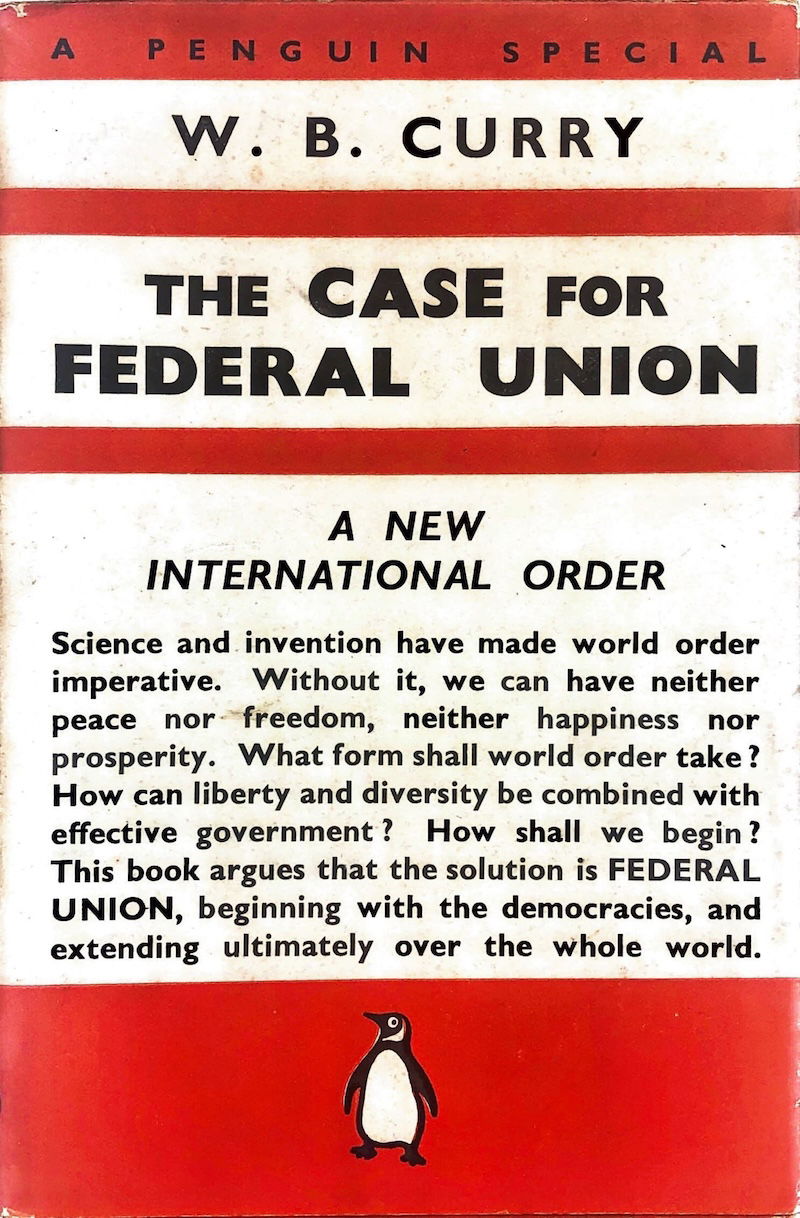

The primary supranationalist organisation in Britain was a group called Federal Union. It sought to create a global federation where powers and responsibilities would be divided between a central authority and its constituent national parts. In this vision, nation states would relinquish sovereignty over foreign and defence policy, but gain greater prizes; not only the strength, both moral and material, that came from unity, but the guarantee of peace and order. Made popular by the work of the American journalist Clarence Streit, whose bestseller Union Now called for a federation of democracies as a bulwark against totalitarianism, by the summer of 1940 Federal Union had 225 branches and 12,500 UK members. Among them were the trade unionist Ernest Bevin, the social scientist William Beveridge and the economist Friedrich Hayek. Its two most prominent Conservative backers were Viscount Astor, the wealthy Anglo-American newspaper proprietor, and Richard Law MP, son of the former Conservative prime minister Andrew Bonar Law.

Law was elected as MP for Hull in 1931. Unlike Astor – forever associated with the pro-appeasement ‘Cliveden set’ – Law had voted against the Munich Agreement. Serving in the army as well as Parliament, he wrote to his colleague Paul Emrys-Evans MP after the declaration of war to express his despair. Having lost two brothers in the First World War, he described lying awake at night thinking of ‘all those killed last time, all those who are going to be killed now’ because of the ‘stubbornness and lack of imagination of a few old men and the supineness of a lot of young ones’. Inspiration, Law argued, was needed.

Speaking in Parliament on 30 November 1939, Law warned of a ‘defeatist attitude’ in Britain and a potential breakdown in morale. To prevent this, he stressed the need to give a clear idea of the ‘kind of Europe we want to erect after the war’. Scorning those who described Federal Union as utopian, Law explained how it was in fact the only solution ‘which recognises that, through the developments of modern science, there has been such a shrinking in the European society that the continuance of independent national States, with their whole sovereignty intact, has become impossible’. Likewise, it was the sole proposal that would resolve the French demand for security with the British need to restore Europe economically. As such, Federal Union ensured the preservation not only of ‘England’ but ‘the whole of Europe and the world, the legacy which has been handed down to us from Greece, Rome and Palestine’.

Law’s civilisational perspective, which placed England furthest along the path of moral and political progress, fitted with how global federation was conceived. Despite the inclination to trace the ideas of world government back to Immanuel Kant and Alexander Hamilton, it was as much the product of British imperialist ideas as European and American democratic ones. Specifically, its origins were intertwined with the dream of imperial federation.

Related to fears of imperial decline in the 1870s, the notion that an imperial federation could hold the Empire together had long attracted Conservatives. Impractical because of a lack of support in the Dominions, by the late 1930s its advocates were becoming supporters of a worldwide federation of democracies. Most notable were Lord Lothian, British Ambassador to Washington, and Lionel Curtis, leading figure in the Royal Institute of International Affairs. For both men a transnational federation operating under Anglo-American (and thus ‘Anglo-Saxon’) leadership was the logical extension of the British Empire.

A ‘Tory Federalist’, Curtis’ planned federation was based on expanding the traditional values of shared destiny, moral brotherhood and self-sacrifice among individuals rather than political or economic equality among states. It thus attracted those who saw federation as a means to maintain rather than disrupt relationships between coloniser and colonised. This was behind Astor’s objections to Federal Union publicity material that indicated a future federal government would be democratically elected and have authority over colonies. Conservative supporters of Federal Union were only willing to go so far when it came to supranationalism.

While the political impetus behind Federal Union died after May 1940, ideas of a potential Anglo-French union and later an Anglo-American one continued to attract Conservatives. Anthony Eden, who had toyed with the idea of coming out for Federal Union, became one of the architects and proponents of the United Nations Organisation. As these initiatives show, the war years were not a period of intellectual morbidity on the right. Rather, it was a time when Conservatives experimented with ideas every bit as radical as those on the left – albeit ones designed to further their own ends.

Kit Kowol is a clerk at the Queensland Parliament, Brisbane and the author of Blue Jerusalem: British Conservatism, Winston Churchill, and the Second World War (Oxford University Press, 2024).