The particularly Pentecostal flavor of Mayra Flores’ Christian nationalism

(RNS) — She is just 36 years old, was born in Mexico, voted for Barack Obama in 2008. But South Texan Mayra Flores just landed herself a spot in Congress on a Republican ticket. Her special election win in June flipped her 84% Hispanic district to red for the first time in more than 150 years. It is an upending Flores relishes.

“Voters in District 34 are realizing we no longer have to beg for scraps from Nancy Pelosi. For over 100 years, the Democrat Party has taken for granted the loyalty and support South Texas has given them for decades,” reads a note on her campaign page.

In addition to many Tejanos, Flores counts plenty of non-Hispanics as fans, including new Texan Elon Musk, who voted Republican “for the first time” to vote for Flores.

Once a vulnerable immigrant child herself, Flores does not champion the “Dreamer” legislation Democrats have repeatedly failed to pass. Instead, Mayra Flores is clear: She is already living her American dream.

“I have risen from working in the cotton fields to representing the community I love in Congress,” she said. Flores describes her victory at the polls as one “for the Lord, my family, our families and for future generations to come.” Flores asserts her loyalties stand to “God, Family, Country | Dios, Familia, Patria.”

In her short time on the national stage, Flores has proved to be a fearless rhetorician for Christian nationalism. “I do believe that pastors should be getting involved in politics and in guiding their congressmen,” Ms. Flores has said. But it is key to note how deftly she expresses Christian nationalismo in Spanish. The aesthetics of her campaign lend little credence to the idea that Christian nationalism is, necessarily, white. Flores’ July Fourth reels feature Tejano music, corn tortilla tacos and numerous American flags. She spent the holiday “celebrando la libertad.”

Flores’ rising star comes as Democrats face daunting 2022 midterms, with surging inflation and slumping support (39%) for President Joe Biden. Though Flores’ term will likely be a short one — she faces a popular Democrat incumbent in a redistricted election in November — her win sends alarming signals about how risky it is to assume Latinx voters will support a Democratic ticket in 2024.

For her part, Flores explicitly portrays herself as Democrats’ worst nightmare: “They claim to be for immigrants. I am an immigrant. They claim to be for women. I am a woman. They claim to be for people of color. I’m someone of color. Yet, I don’t feel the love.” Democrats, she counters, “are destroying the American dream.”

Latinx votes for Republicans upset the media optics that cast Republicans as the party of white nationalism and Democrats as a racially diverse coalition. But there’s good reason to think religion, not race, best explains Flores’ successful campaign.

Two days before her election, Flores posted pictures featuring her at the center of a group in prayer. “These are pastors from South Texas praying over me and our campaign efforts. … It’s time to elect GODLY people who reflect our morals and values according to the Word of God. … Thank you Pastors for being involved in your civic duties.”

The pictures are reminiscent of images showing Donald Trump being similarly prayed for by groups of pastors convened by Paula White. In Flores’ picture, hands are stretched toward her. Others are laid on her shoulders; one is on her forehead. The gathered crowd appears to be composed of both Latinos and non-Latinos, women and men. Behind Flores’ head, a campaign poster reads, “Make America Godly Again.”

In the caption for this post, Flores thanks just one pastor for his prayers and guidance. Luis Cabrera is pastor of City Church in Harlingen, Texas. The church’s most recent Facebook posts document its July Fourth festivities, complete with red, white and blue balloons, tiny American flags to wave and nearly everyone in “Make America Godly Again” T-shirts. Another image has 2 Corinthians 3:17, “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is Freedom,” splashed across a flag motif: a doubling of the idea of biblical freedom with political freedoms.

The church’s website suggests it is Zionist and affirms the biblical gifts of the Holy Spirit, including those in Acts 2, which are key to Pentecostal claims that the baptism of the Holy Spirit (i.e., speaking in tongues) is for practice in the present day. Crystal Cabrera, Luis’ wife, went to Southwestern Assemblies of God University, part of the second-largest Pentecostal denomination in the U.S. Like Paula White’s Florida church, City Church appears to be “nondenominational” in name but Pentecostal in practice.

According to political scientist Ryan Burge, Pentecostals poll more Christian nationalist than any other religious group — but they are an impressively multiethnic group. Burge notes that membership of the Assemblies of God has become more politically conservative and more religiously active today than just a decade ago, even while it has achieved an enviable degree of racial diversity — 44% of members in the United States are ethnic minorities. If Pentecostals are the most Christian nationalist religious group, it may be misleading to think of Christian nationalism as by definition “white.” Sociologist Jonathan Calvillo finds that Latinx Protestants identify more with the U.S. than their prior home countries. Ethnic minorities who are Pentecostals are very likely to vote for a Christian nationalist agenda.

The comments replying to Flores’ Instagram posts are overwhelmingly religious in tone. But they come from ethnically and denominationally diverse supporters. In addition to fans in Texas like Joshua Navarrete, a Pentecostal minister, Flores has received support from the Rev. Frank Pavone, a high-profile Catholic priest from Florida, who is currently head of ProLife Voices for Trump.

Yet, if 2020 taught analysts anything about the Latinx vote, it is to expect surprising divergences among Florida, Texas and California voters. In 2020, Latinx dollars overwhelmingly went to Bernie Sanders, at nearly four times more than any other Democratic candidate; California later went to Biden, while Florida’s and Texas’ Hispanic contingencies went for Trump.

Such demonstrated preferences actually suggest the strength of anti-party, populist rhetoric with today’s borderland Latinx voters. In their campaigns, both Sanders and Trump expressed animus toward establishment politicians, whom Trump called “the swamp,” and the wealthy donor class that keeps such politicians in power, and Sanders called “the 1%.” Both candidates asserted their outsider status and reluctance to run in party primaries.

Flores’ campaign advanced similar messaging. And, by early indications, so will her tenure.

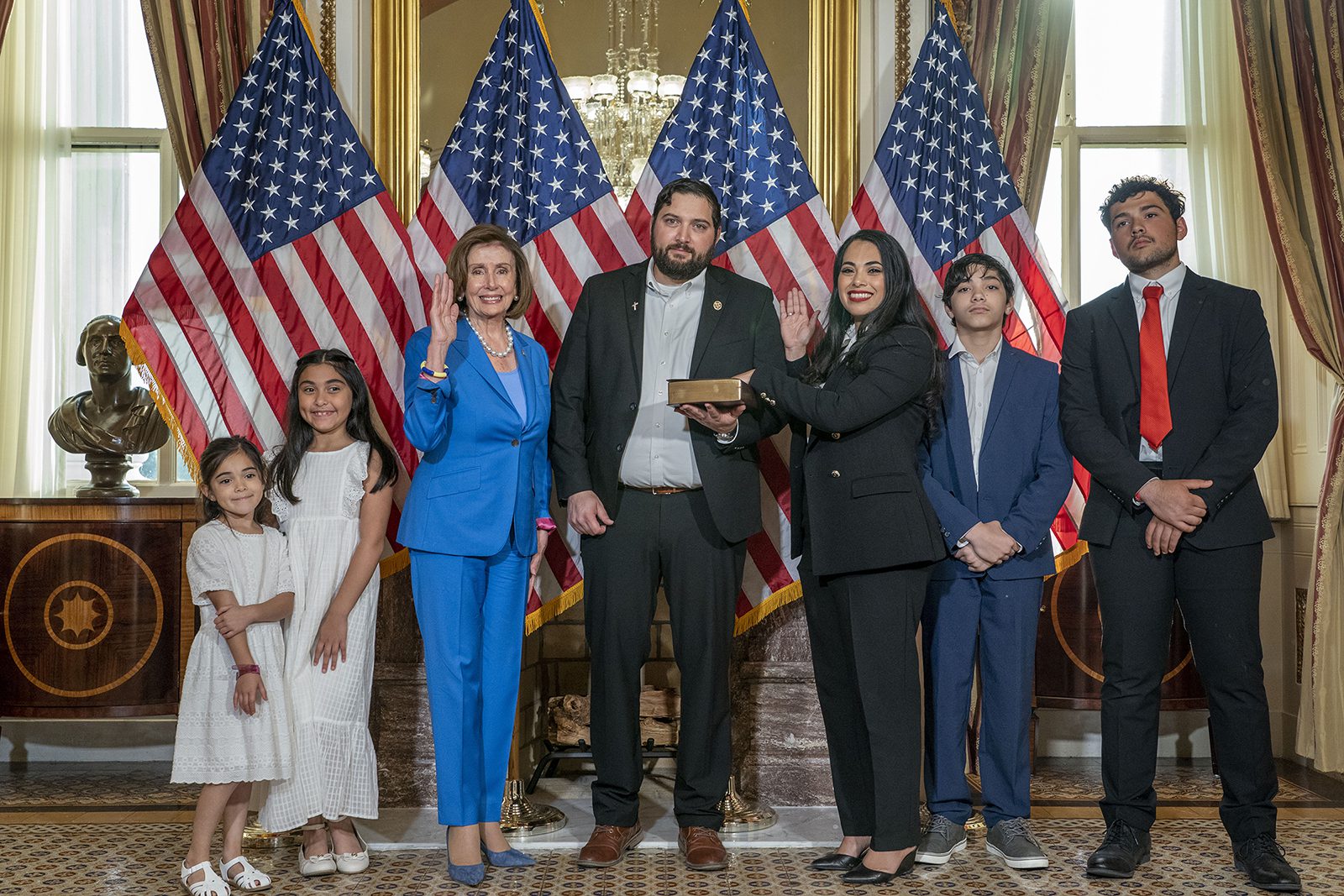

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi administers the House oath to Rep. Mayra Flores, R-Texas, center right, as her husband, John, holds the Bible, during a mock swearing-in ceremony at the Capitol in Washington, June 21, 2022, with children, from left, Milani, 6, Maite, 8, Jaden, 12, and John Michael, 16. (AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe)

She turned her swearing-in ceremony into a grievance drama, accusing House Speaker Pelosi of elbowing her daughter aside to make more room for herself during picture-taking. In videos of the exchange, Flores’ daughter seems confused by Pelosi’s maneuver and stays put in the same place. Flores later posted: “I am so proud of my strong, beautiful daughter for not allowing this to faze her. She continued to smile and pose for the picture like a Queen. No child should be pushed to the side for a photo op. PERIOD!!” The post has more than 180,000 “likes.”

While posts like Flores’ might seem rude to many readers, for Pentecostals, performing political disrespect has long been a sign of spiritual virtue. Since the beginning of the movement, Pentecostals have equated being elite with being insufficiently godly. In this exchange, Pelosi fell unwittingly into the role of an elite antagonist, assuming her right to pride of comfortable place.

Fox News describes little Maite Flores as “promptly taking back her spot and teaching us all a lesson in what it means to be American: equal in worth under the law, and unafraid of the arrogant and the powerful.” The title of the article echoes Flores’ own rhetoric: “A Tejana ‘Queen’ shows Pelosi and America that Hispanics won’t be pushed around anymore.”

Such antagonism for elites is a signal to populist voters that their candidate remains impervious to the lures of Washington power brokers. If Washington’s laws are deemed evil by biblical standards, such antagonism demonstrates the candidate has not been compromised. In such a context, Pentecostals do not perceive a contradiction between antagonistic humor and biblical morality. On the contrary Pentecostals, at last look near 25% of the U.S. population, are readily mobilized by a combination of anti-elitist animus and Christian nationalist themes.

“Tejana Queen” is a far cry from “bad hombres,” “rapists,” “thugs” and “animals,” all monikers Trump parlayed against the undocumented crossing the Southern border. But the change in terms is likely to suit Latinx Pentecostal supporters superbly well. Pentecostals often anoint their candidates with popularly derived sovereignty. Like Trump, who became King Cyrus, and Sarah Palin, who became Queen Esther, Mayra Flores has been called to Washington. Her authorization comes from a power higher than Pelosi, instead conferred in that prayer circle by the laying on of hands.

If it means more Latinx votes, Fox will happily play along.

But Flores’ deployment of populist rhetoric comes at real cost.

U.S. populism has long centered on the notion of peoplehood. If Republicans seem willing to allow the likes of Flores into “the American people,” will Flores minimize the fact that among the dead found in a truck in San Antonio last month lay 53 Latinx immigrants, whose hopes and dreams perished with them? Some may have been Mexican Pentecostals like her, who prayed for safe travel across a brutal border.

On a different route, on a less tragic day, one might have ended up serving her lunch. Another might have shown up in her pew. As Dan Ramirez notes, on any given Sunday undocumented believers head to hundreds of charismatic churches, seamlessly blending in. In shilling for Republicans, Flores has a hand in normalizing a deadly border that, for Tejanos, will always require the sacrifice of common feelings for fellow Latinx in the duress of crossing.

Just who are Flores’ people? Time will tell.

(Erica Ramirez is a sociologist of religion at Auburn Theological Seminary in Manhattan, a fifth-generation Texan and a graduate of Southwestern Assemblies of God University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)