A new exhibit showcases a Muslim POW camp

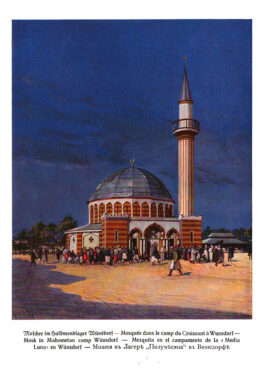

(RNS) — In 1915, Germany’s first mosque was constructed from wood in a WWI Muslim prisoner of war camp. Likely built by the prisoners themselves, the mosque was a mishmash of Islamic architecture, with its dome, façade and minaret each representing different regions of the Islamic world.

The patchwork approach wasn’t accidental. It embodied a German/Ottoman propaganda campaign that sought to “woo” Muslim prisoners from around the globe to overthrow the Russian, French and British empires. Though the mosque and its story are unfamiliar to many students of the first World War, Patricia Cecil, specialist curator of faith, religion and WWI at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, argues that they are a testament to the war’s scale and impact.

“We conceive of it as this very European war. But it wasn’t. It was a global war,” Cecil told Religion News Service. “And this camp is evidence of that, and the photographs we have are evidence of that.”

Photograph of North African French colonial prisoners of war at Halbmondlager, “Half Moon Camp,” in Wünsdorf, Germany, in 1915. (Print, Photograph from periodical “Der Grosse Krieg in Bildern,” No. 4. 1915. Germany. 2007.68.4. National WWI Museum and Memorial.)

A new online exhibit launched Thursday (Jan. 26) by the National WWI Museum and Memorial presents the overlooked story of the Halbmondlager, or “Half Moon Camp,” a Muslim prisoner of war camp located in Wünsdorf, Germany. Featuring propaganda newspapers, photographs of the prisoners and audio clips of them playing instruments and reading poems, the “Fighting with Faith” exhibit captures a moment in history whose reverberations are still felt throughout the modern world.

At the camp, prisoners from as far away as West Africa and South and Central Asia were provided with halal foods, permitted to worship, allowed to observe religious rituals and holidays and visited by lecturers and foreign dignitaries who urged global Islamic solidarity. They were also given extra rations and larger sanitary facilities than prisoners at other German camps and were provided with extra leisure time for activities like attending concerts and playing cards. But though these perks might have appeared generous, Germany and the Ottoman Empire had ulterior motives, according to Cecil.

Illustration of the mosque at Halbmondlager, “Half Moon Camp.”

(Illustration from Die Kriegsgefangenen in Deutschland, Siegen, 1915. Germany.)

“From the outset, using religion as a tool of propaganda was the goal,” said Cecil. “They wanted to have the benefit of millions of Muslim soldiers. If you can get all these people currently under the rule of the British, French and Russian empires, and can get them to side with a religious ideology that also aligns with your military ideology, you have a recipe for revolution across the world.”

The exhibit explains that in 1914, German actors and Ottoman leaders influenced the sultan of the Ottoman Empire — who was also caliph, or head of the worldwide Islamic community — to declare a jihad, framing the war against the allied powers as a sacred obligation for all Muslims. By giving Muslim prisoners special treatment at the camp, Germany and the Ottoman Empire hoped to entice prisoners to join the politically motivated jihad.

The ploy, by most measures, failed, said Cecil. Those who did opt in to the Ottoman military were mistreated and often ended up deserting — letters show that some wrote back to the camp to warn about being abused by Ottoman officers. But more significantly, the prisoners were largely unconvinced by the German and Ottoman tactics.

“Their own national ties, ethnic ties and understanding of Islam and what it teaches about jihad were stronger than propaganda,” said Cecil. “This failed because Germany and the Ottoman Empire couldn’t get this group of Muslim prisoners of war to align with what their idea of jihad is.”

“Fighting with Faith” online exhibit logo. Image courtesy National WWI Museum and Memorial

But though the propaganda campaign itself was a failure, it left its mark. “This alliance, this propaganda campaign, and this camp, if we want to drill it down, is the birth of the Western notion of jihad for the 20th and now the 21st century,” Cecil told RNS. Jihad has several meanings, including an internal struggle to honor the divine or external struggle against the enemies of Islam. But Cecil argues that this was the first time jihad was linked to a geopolitical military ideal: to overthrow the British, French and Russian empires.

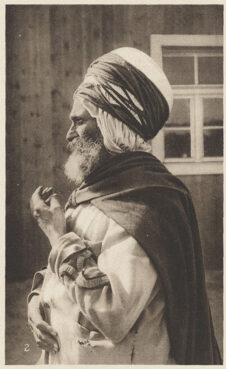

Photograph of a Saphi prisoner of war at Halbmondlager in 1915. (Print, Photograph from periodical “Der Grosse Krieg in Bildern,” No. 4. 1915. Germany. 2007.68.4. National WWI Museum and Memorial.)

Cecil added that the failed campaign also had lasting effects on the Middle East. Prompted by the perceived threat of a holy war, Great Britain diverted soldiers and resources to the Middle East and deepened its involvement in the region both during and after the war. The propaganda campaign also led to the Sykes-Picot Agreement, the exhibit argues, which fractured and redrew the Middle East, laying the groundwork for discord in the region for decades to come.

“The whole 20th century is affected by World War I,” Leila Fawaz, chair of Lebanese and Eastern Mediterranean studies at Tufts University, told RNS. “The fact that this museum took the challenge to study this incredible subject, which much more experienced experts on the region have never gone near, is extraordinary.”

Fawaz, who previewed the exhibit, appreciated the museum’s attention to the prisoners, rather than just to global actors.

“I’ve always liked the story of the little people, not the powerful people. It’s really easy to write about the great powers … but it’s the common people that I’m interested in.”

The exhibit, which will be online indefinitely, complements an onsite exhibit on WWI prisoners of war at the museum in Kansas City, Missouri. “Fighting with Faith” is free online and is funded by the Lilly Endowment, which is also a key supporter of Religion News Service.